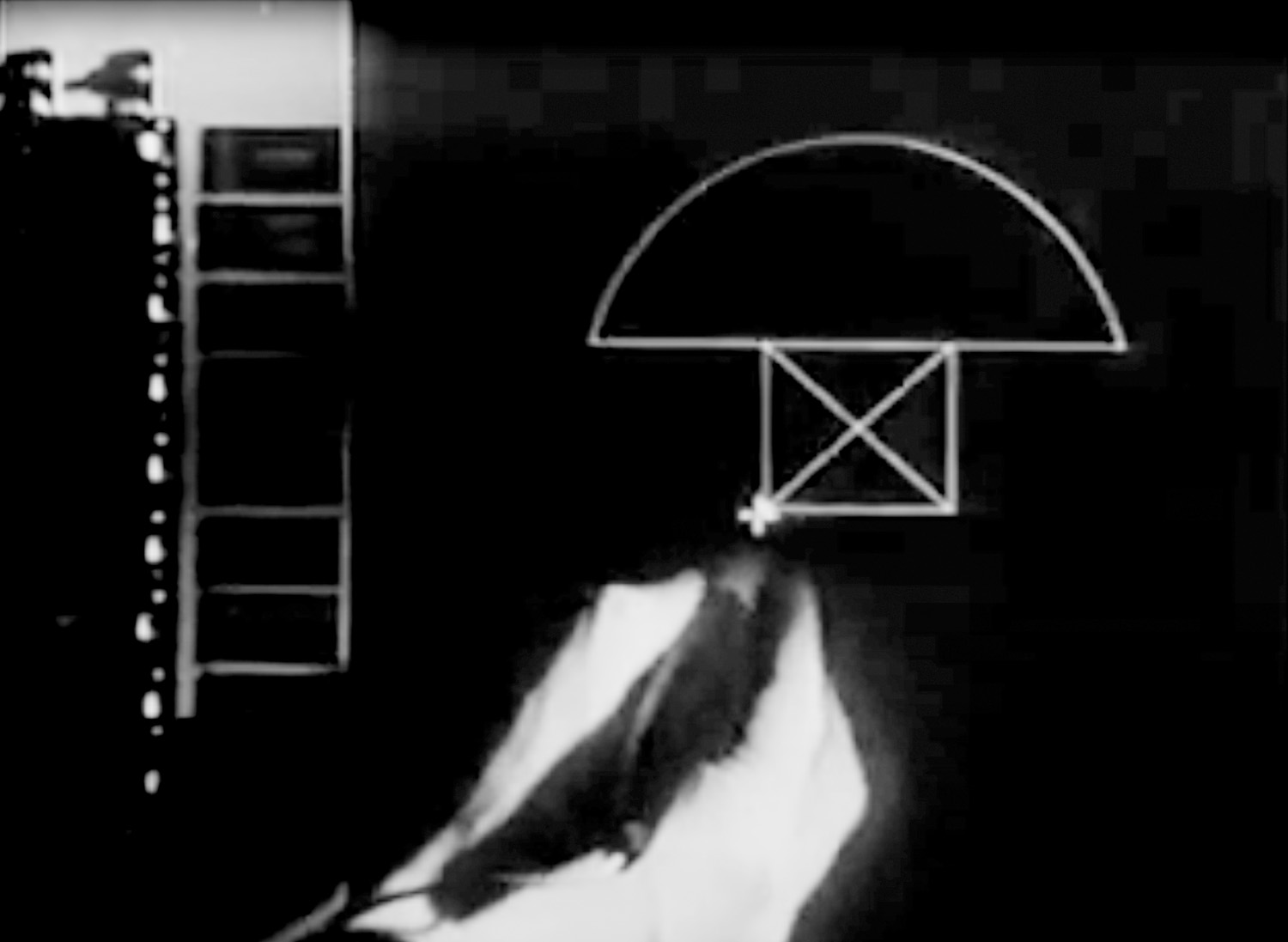

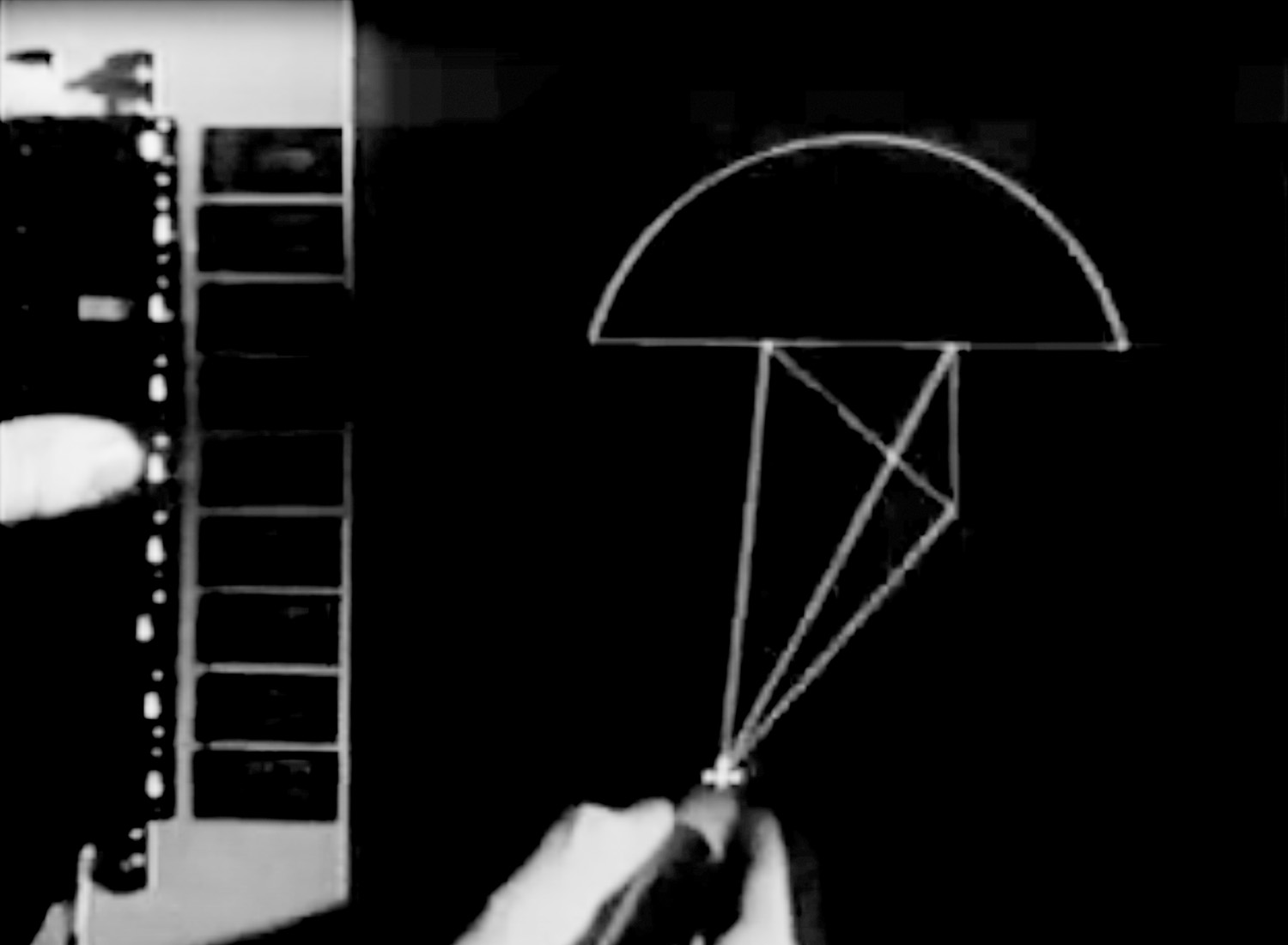

At the time of writing, my Google Doc offers me the option of configuring my document in “Pageless” mode. Forty years after the appearance of the first word processing software, this symbolizes the shift towards the paradigm of an interface that is almost totally free of references to print and paper. Looking back on the history of graphic interfaces, one can see a consistent desire to reproduce existing media models. As early as 1961, Sketchpad, the first graphical user interface, conceived by engineer Ivan Sutherland, displayed a flashing “INK” icon on its blank “pages.”11 Term used in 1963 in a Sketchpad presentation video created by MIT at the Lincoln Lab in Lexington. See: Ivan Sutherland Sketchpad Demo 1963, http://b-o.fr/sketchpad

Sutherland was using a RAND Tablet, a direct interface using a luminous free-hand stylus one could use to write on a screen with what its designers termed as “digital ink.”22 M. Mitchell Waldrop, The Dream Machine: J.C.R. Licklider and the Revolution That Made Computing Personal, (New York: Penguin,2001), 239. The computer with which Sketchpad was developed, the TX-2, is a machine over six meters long, whose control panel was covered with a multitude of buttons, cursors and dials, along with a small (25 cm square) screen.

Sutherland was using a RAND Tablet, a direct interface using a luminous free-hand stylus one could use to write on a screen with what its designers termed as “digital ink.”22 M. Mitchell Waldrop, The Dream Machine: J.C.R. Licklider and the Revolution That Made Computing Personal, (New York: Penguin,2001), 239. The computer with which Sketchpad was developed, the TX-2, is a machine over six meters long, whose control panel was covered with a multitude of buttons, cursors and dials, along with a small (25 cm square) screen. The proportion between the graphic interface of the screen and the physical interface with the object is at the opposite end of the spectrum of our current smartphones. The screen was entirely dedicated to drawing and presented no buttons or menus. In order to execute the literally digital commands (i.e. to make two lines parallel, duplicate an object, enhance a view, etc.), the operator would have to manipulate a series of material elements (buttons, dials, etc.). This foundational experience has left us with the temptation to reproduce physical objects on the screen: images of switches, dials, or cursors.

The proportion between the graphic interface of the screen and the physical interface with the object is at the opposite end of the spectrum of our current smartphones. The screen was entirely dedicated to drawing and presented no buttons or menus. In order to execute the literally digital commands (i.e. to make two lines parallel, duplicate an object, enhance a view, etc.), the operator would have to manipulate a series of material elements (buttons, dials, etc.). This foundational experience has left us with the temptation to reproduce physical objects on the screen: images of switches, dials, or cursors.

A decade later, teams at the California research center Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center), formulated the