First things first: I am not the author of “the first GIF ever,” despite Google’s misinterpretation of my words, or the retro black-and-white esthetics of the first ever animated GIF I made.11 See the article by Fernando Alfonso III, “The Animated History of the GIF, the Internet’s Favorite Format,” Dailydot, (June 2015), which is responsible for the confusion, http://b-o.fr/alfonso This myth began to spread through articles and forums and made it back to the top Google search results. I am being introduced as the creator of GIFs and, within a few years, will probably enter the annals of history as the founder of this format. To counter this, I would like to finally put in zeros and ones my answer to the frequent question, “Did you really made the first GIF ever?” which is “No, of course not!” The format had been around for almost a decade: ten months before the Window.gif  was published in 1996 everyone and their sibling was making and using them on the Web. GIFs were already beginning to be questioned and mocked as early as the last half of 1996, and it was only one year after that before they began to be abandoned and erased.

was published in 1996 everyone and their sibling was making and using them on the Web. GIFs were already beginning to be questioned and mocked as early as the last half of 1996, and it was only one year after that before they began to be abandoned and erased.

This timeline was still present in cultural memory a decade ago, but in 2020 one must specifically make mention of it, in order to remember what came before animated GIFs made their glorious comeback during the first wave of “netstalgia” in the early 2010s.22 For more on the topic of “netstalgia,” see Olia Lialina, GeoCities’ Afterlife and Web History, (2019), http://b-o.fr/geocities The Web is getting older: older than PhD candidates writing about its history, which is evolving in an increasingly homogeneous manner. Web users and researchers develop shortsightedness very quickly, and not just because they spend a lot of time in front of a screen. We are still under the curse of “Netscape Time,” the paradigm in which everything changes rapidly and is updated radically, thus deleting previous versions of everything from memory (be it computer or human).33 “‘Netscape Time’ was a term we came to apply to the speed at which we developed products and, by extension, the relentlessness of the work involved. But the effortlessness of Web use is also an aspect of Netscape Time,” James H. Clark, Netscape Time, (New York: St Martin’s Press, 2000), 65. Online, everything that is not here and now constitutes history. The years 2006 and 2016 are as distant in memory as is the year 1996. GeoCities, Myspace, and Tumbler all constitute that which existed before let’s say, TikTok, and, in a year or two, TikTok will be superceded by the next new killer app.

Along with the rapid turnover of applications and services, the way we perceive the World Wide Web also evolves, but generally we do not perceive it. The Web has become the underlying technology for many other things—apps, experiences, AI—even as it has lost its significance and power as new media. Seen in this context, it is fascinating to see how the file format that was an essential part of the Web when it was being established as a new medium has become a medium in and of itself, even as its parent is fading into the realms of invisible technology.

GIFs both emancipated and outlived the Web. Researchers today contextualize this “new medium” using the history of cinema and pre-cinema. They make bridges to other disciplines such as feminism, cyber-feminism, and metamodernism, and see it as a symbol and manifestation of society at large, a sort of circle of life. In 2016, Monica Dall’Asta posited nothing less than the idea that GIFs “mimic on a formal level the blocked dialectic of capitalism, [and] its incessant pursuit of change that never changes anything.”44 Monica Dall’Asta, “GIF Art in the Metamodernist Era,” Cinéma&Cie, (Milano: Mimesis International, 2016), 82.

Looped animations are recognized and celebrated in different historical and media contexts, and also as a field for artistic practice. They even have genres: cinemagraph, reaction, boomerang, sticker, sound GIFs,55 On the 28th of July 2011, u/squidbrain posted the following query on Reddit “Can you get .gifs with sound?,” http://b-o.fr/reddit. This innocent question triggered an avalanche of jokes and became a meme. Some months later https://gifsound.com/ was born as a direct answer to the post. I discuss the development of this trend at the end of the article. There are GIF exhibitions, and a GIF culture. Yes! We have GIF artists and artists who put a “My GIFs” button in their portfolios. As a net artist and self-proclaimed animated GIF model, this makes me very happy. Still, according to Sofya Aleynikova in The Perfect GIF:

users […] reduce their GIFs to a mere reference to another, more dominant format, the motion picture or video clip; GIFs find themselves subjected to the media-specific parameters of the latter, while people forget that a GIF is [first and] foremost one thing: a looped graphic on a website.66 Sofya Aleynikova, The Perfect GIF, 2014, http://b-o.fr/Aleynikova

Indeed, when we evoke GIFs, we are dealing with so many different things—from techniques and the esthetics of loops to politics—but we hardly discuss the Web, and that is a mistake. The WWW is the best thing that ever happened to the Internet and all of us. The early Web was an environment where those without programming skills could execute and demonstrate their programming power, one where people were building cyberspace. Twenty years ago, when I started to collect and monumentalize GIFs, I did it to celebrate and commemorate the efforts made by these early creators of the Web.

In order not to lose sight of its history, as well as to potentially regain the powers we could still exercise upon the Web in 2020, it is even more important than in 2000:

—to talk about GIFs as a file format, not a medium;

—to discuss them as elements of websites, not simply objects to be posted and embedded;

—to see them within the context of Web browsers, not outside;

—to talk about transparency, not just animation and loop;

—to stop asking what was the first GIF ever, because it is not important.

Let us imagine that we agree upon this. For those who are still on a mission to find the earliest GIFs, I suggest they flip through Compuserve magazine, starting from the end of 198777 Online at The Internet Archive (accessed December 2020), http://b-o.fr/compuserve-magazine There you can find the original thoughts of GIF developers, descriptions of the format, and examples. They are curious, but they are more about the history of Compuserve, not the WWW. So I will skip it.

For me, the story begins in 1995. I would quote from the book GIF Animation Studio, written in 1996, one of the first books that explained GIF animations to Web developers. Before beginning with the how-tos, they rightfully pointed to the then short, but glorious history of the format, the grassroots origins of the “animation explosion”:

GIF animation is a real grassroots net story. Netscape implemented support for GIF animation, but didn’t tell anyone. Individuals investigating the GIF standard who discovered Netscape had implemented GIF animation […] put the word out about how to create GIF animations.88 Richard Koman, GIF Animation Studio: Animating Your Web Site, (Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media, 1996), 3.

Andrew Leonard told the story in his February 1996 column in Web Review. The column itself is long gone, but remains accessible today through the Wayback Machine:

The Net community still remained in the GIF animation dark. Enter Royal Frazier. One night in December, while playing around with the shareware program GIF Constructor Set, Frazier […] discovered the animation possibilities built into the GIF89a spec. […] The response to [his] discovery had been ‘extremely enthusiastic,’ says Frazier with a chuckle. So much so, in fact, that Frazier’s been forced to scramble for mirror sites for his GIF89a webpages, which at last count were at 2,000 hits a day and rising.99 Andrew Leonard, Grassroots Tech. Anatomy of Animation Explosion, 1996, http://b-o.fr/leonard

The story also mentions the VRML GIF  created in December 1995 by Jim Race, not as an example of a first, but rather as one that gained popularity and spread quickly.1010 Jim Race, VRML From HELL, started 1995, http://b-o.fr/vrml It is curious that this particular graphic was a harbinger of the future of the Web, and the story continues, twenty-five years later, with 3D and VR. It also reminds us of the role attributed to animated GIFs at the time, namely as placeholders for the multimedia future, whose arrival was deemed imminent.1111 See: Olia Lialina, This May Take Up to 20 Seconds, http://b-o.fr/lialina

created in December 1995 by Jim Race, not as an example of a first, but rather as one that gained popularity and spread quickly.1010 Jim Race, VRML From HELL, started 1995, http://b-o.fr/vrml It is curious that this particular graphic was a harbinger of the future of the Web, and the story continues, twenty-five years later, with 3D and VR. It also reminds us of the role attributed to animated GIFs at the time, namely as placeholders for the multimedia future, whose arrival was deemed imminent.1111 See: Olia Lialina, This May Take Up to 20 Seconds, http://b-o.fr/lialina

The curious user Royal Frazier remains relatively unknown today, though his elegant email.gif  is still out there. However, he should be remembered, as both an artist and the one who spread the word about GIFs, but first and foremost as a passionate webmaster who built the first GIF gallery. At the bottom of the gallery’s page he reminisces thus:

is still out there. However, he should be remembered, as both an artist and the one who spread the word about GIFs, but first and foremost as a passionate webmaster who built the first GIF gallery. At the bottom of the gallery’s page he reminisces thus:

This gallery was the first to feature the use of GIF animation on the Internet, in January 1996. It will always be the oldest promoter of GIF animation; it can be considered the Granddaddy of them all. The goal was to highlight the possibilities and give credit to the people who built the animations. Even now, I find most animation collections claim GIFs to be public domain when they are not. Providing credit and [establishing] links back to the animators and their sites was important in the design. However this site became very outdated, with many dead links. It has since been discontinued1212 Royal Frazier, GIF89a-Based Animation for the WWW, 1998, http://b-o.fr/frazier

In February 1996, when Netscape finally went public about GIFs, they linked to Frazier’s collection from their Assistance page, citing it as a primary source from which one could learn more about animated GIFs.1313 http://b-o.fr/animated-gifs This, in itself, is a great story of the grassroots (democratic, horizontal, hyperlinked) Web of the mid-1990s, when browser creators linked to webpage makers, who, in turn, would list search engines and other useful links.

Free GIF collections, along with collections of backgrounds, sounds, and scripts, played a crucial role in Web growth. Let me mention some legendary ones, to begin with: Celine’s Original GIFs was the generous effort of self-taught Web designer Celine Chamberlin to place her graphics willfully and knowingly in the public domain, thus providing users with free rein to download, use and/or change these graphics for their own use in their webpages.1414 Celine Chamberlin, Celine’s Original .gifs Index, http://b-o.fr/celine Icon Bazaar  consists of graphics made by Randy D. Ralph himself along with ones he found on the Internet.

consists of graphics made by Randy D. Ralph himself along with ones he found on the Internet.

As he states:

The copyright status of the collected and contributed images can be questionable. To the best of the developer’s knowledge they are in the public domain. Use them at your own risk.1515 Randy D. Ralph, Icon Bazaar, http://b-o.fr/icon-bazaar

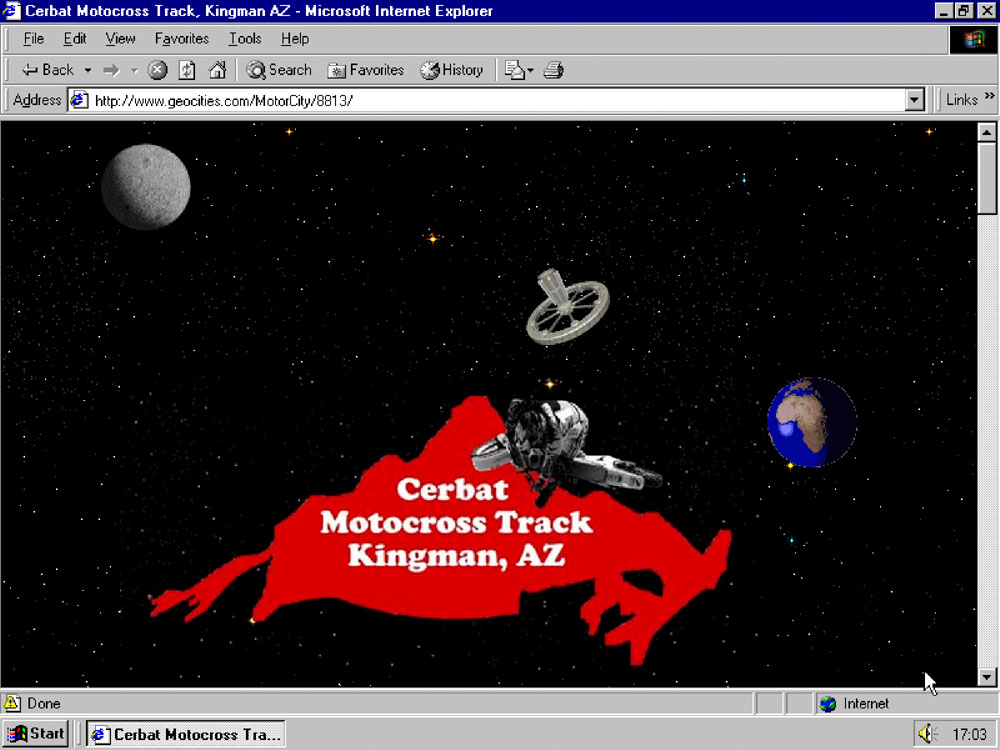

Astrophysicists and Cyberspace veterans Lucy and Alan Richmond left NASA to start Star.com, a virtual library for web developers, or rather a portal where their contemporaries could find links to everything one would need to make a multimedia website.1616 The story of the creation of Lucy and Alan Richmond’s site Stars.com is documented at http://b-o.fr/richmond Today, this source remains a treasure trove for researchers of Web history. It was at Stars.com that I found the origins of the graphic used on so many early webpages: “the earth rotating, Northern hemisphere only, as viewed from your spaceship high above earth.”1717 http://b-o.fr/graphics  Let’s see if you are able to find it as well.

Let’s see if you are able to find it as well.

Most of the collections contained general interest graphics. For example, Aviation Animations featured a large number of GIFs (“at least 324”), that were focused on specific subjects.1818 J. Self, Aviation Animation, http://b-o.fr/aviation-menu Most of them are long gone, but some are archived and accessible at Archive.com. Some of the older ones are still online (as of November 2020): take your chances and visit Karine’s GIF ART.  Also consider immersing yourself in what remains of Sonya Marvel’s collection, which was started in 1996 and is currently accessible on Tripod. She was a set maker, meaning she provided a combination of backgrounds, buttons, bullets and rules rather than individual graphics.

Also consider immersing yourself in what remains of Sonya Marvel’s collection, which was started in 1996 and is currently accessible on Tripod. She was a set maker, meaning she provided a combination of backgrounds, buttons, bullets and rules rather than individual graphics.  It was the next step in the history of Web design, and one that requires its own essay, but I wanted to mention it here because elements from her collection can still be found all over the Web and are used outside of the sets and layouts she suggested.

It was the next step in the history of Web design, and one that requires its own essay, but I wanted to mention it here because elements from her collection can still be found all over the Web and are used outside of the sets and layouts she suggested.

The GeoCities archive features a lot of pages that were made for the sole purpose of archiving and providing access to GIFs. There were even more Web designers for whom “My GIFs” was just another position in the menu. The author of the page might mean that the graphics were designed by them “from scratch,” or that they did the animation, or maybe simply sourced and collected them.1919 See: Olia Lialina, All the Animations Were Mine. None of the Graphics Were, 2014, http://b-o.fr/lialina2. See also: “From My to Me,” in Olia Lialina, Turing Complete User: Resisting Alienation in Human Computer Interaction, arthistoricum.net, 2021, http://b-o.fr/mytome In the context of this essay it is important to emphasize that every webpage was (or could have been seen and used as) a free collection. Making a webpage meant that you were automatically providing elements to others—whether willingly or unwillingly—thanks to the modular and open architecture of HTML pages. Consequently, you might make a GIF for your homepage, then see it next day on another page or, better still, find it on other pages twenty years later. GIF files played a crucial role in facilitating the model where one could forge a website from the elements taken from another one. To understand this, one should forget for a moment that when we say GIF we mean animated GIF.

The early Web was full of static GIFs. In the 1990s, developers and users were excited about its other magic feature: namely transparency, i.e. “images [that] look as if they are floating on the page.”2020 Jason J. Manger, Netscape Navigator, (New York: McGraw-Hill Osborne Media, 1995), 132. In 1998, Roy McKelvey writes about transparent GIF files in the Hyper Graphics catalog:

[They are] a primary tool for achieving visual complexity while keeping file sizes within limits […]. The GIF89a allows for the creation of files with one color set to transparency… As a result, complex relationships between text and image or between image and image can be created without having to treat the entire page as one immense graphic.2121 Roy McKelvey, Hyper Graphics, (Brighton: RotoVision SA, 1998), 54.

In 1996, in his book Creating Killer Web Sites, David Siegel stated that “properly antialiased images with transparency are the basic building blocks of a third-generation site”2222 David Siegel, Creating Killer Web Sites: The Art of Third-Generation Site Design, (Indianapolis: Hayden Books, 1996), 52. and called for designers to benefit from the feature. They didn’t listen. As early as 1997, professional webpages had turned into Photoshop images, cut into parts (or not), and reassembled in the browser.2323 The Photoshop website phenomena is first discussed in the Free Collections of Web Elements chapter in Olia Lialina, A Vernacular Web, 2005, http://b-o.fr/lialina3 It was a strategy that could not continue for long since such websites had to be redesigned every time they required an update. However, an urge to look more like a product and less like a free collection was pushing web design in that direction.

Some GIFs are static: they are scans, saved as JPEGs and turned into GIFs afterwards,  like sailormoon.gif and scully.gif. They become part of a collage, allowing the authors of the pages to experiment with background colors and wallpapers and change them frequently, and of course to make a graphic spread. All this because, despite divergence over questions of copyright—whether free, linkware, shareware, or if you believe that copying is stealing— there was consensus regarding the answer to the question: “how many Sailor Moon and Scully fan pages can cyberspace endure?” The unanimous answer: an infinity.

like sailormoon.gif and scully.gif. They become part of a collage, allowing the authors of the pages to experiment with background colors and wallpapers and change them frequently, and of course to make a graphic spread. All this because, despite divergence over questions of copyright—whether free, linkware, shareware, or if you believe that copying is stealing— there was consensus regarding the answer to the question: “how many Sailor Moon and Scully fan pages can cyberspace endure?” The unanimous answer: an infinity.

Transparent, also known as cutout GIFs—be they animated or not—easily made their way from one page to another. The same GIFs were to be found on different pages and, depending on the context, i.e. content of the page and the element with which they were associated in the dialog, their meanings would change. The notorious Peeman figure is known primarily for being used to express disgust or disagreement, whether in politics, culture, sports, or on a personal level. Yet, on some pages, the same figure signifies a fireman. Also, when used alone, the character could simply be used as a horizontal ruler to evoke a range of meanings, from Alpha Male to “Just Kidding.”2424 See the research and exhibition entitled What Did Peeman Pee On, http://b-o.fr/peeman  It was similar to the way people used Felix the Cat2525 More about Felix in Dragan Espenschied, What Felix Stands For, 2011, http://b-o.fr/felix

It was similar to the way people used Felix the Cat2525 More about Felix in Dragan Espenschied, What Felix Stands For, 2011, http://b-o.fr/felix  : as a symbol for depression, but also relief, and even as a substitute for an Under Construction icon.2626 If not familiar with the mainstream Under Construction, visit Jason Scott’s collection, Please Be Patient—This Page Is Under Construction!, http://b-o.fr/underconstruction

: as a symbol for depression, but also relief, and even as a substitute for an Under Construction icon.2626 If not familiar with the mainstream Under Construction, visit Jason Scott’s collection, Please Be Patient—This Page Is Under Construction!, http://b-o.fr/underconstruction

There was also another type of transparent GIF that was important if not crucial to web design. Namely the invisible pixel, or a clear GIF2727 For more about transparent GIFs see Trevor Owens, The Invention and Dissemination of the Transparent GIF: Traces in Web Archives, http://b-o.fr/owens. Also see my talk, Transparency, given at Import Projects, Berlin, 2013, http://b-o.fr/lialina-talk. My Clear GIF collection is stored and maintained by Evan Roth at http://b-o.fr/clear-gif —that could be positioned between two elements and stretched to as many pixels as you would need to create space between those elements. The role of this invisible element on the vernacular Web as well as the role of the legions of anonymous or forgotten users who turned JPEGs into transparent GIFs is difficult to overestimate, but unfortunately very easy to overlook.

Let’s return to the subject of animation and specifically, the GIF Animation Studio book. Right on the second page, the authors claimed five major advantages of the format, as perceived in 1996:

—Users needed no special software: there was no need to install any plug-ins. All one needed was a browser that supported GIF animation.2828 Koman, op. cit., 2.

—Standard file format: GIFs are recognized by all browsers. Even if one happened to use one which was not, it would show the first frame, not an error message. One error message less to see online!

—Ease of creation, at least on Macintosh: the authors felt they had to mention it; I can attest that it was really not a big deal and it was also a lot of fun to make a GIF on Windows in 1996.

—Streaming technology: you do not have to wait until a complete file loads on your screen—as soon as each frame is done, it displays.

—Easy on Web servers: GIF animation delivers exactly one hit on the server, the browser takes care of the rest.

These assets may seem archaic or naive a quarter of a century later, when software installs itself in the background, and we stream video live 24/7 and do not even know that objects onscreen or elsewhere contain files of different formats, but essentially, they still apply. This list is also a reminder that Web browsers are animated GIF’s only stage, the engine that sets them in motion. Outside of the browser, GIFs are frames with instructions, props piled backstage, to use a theatrical metaphor. A Web browser displays them, it counts the milliseconds between frames, and takes care of transparency and looping.

As a Web user and Internet artist for the last twenty-five years, I am very attached to and dependent upon browsers. They are my stage, my gallery, my studio, and, since I am also a GIF model, my catwalk. I have a fear of losing this environment, afraid of being confined to some GIF or Internet art app instead. Nonetheless, observing the mainstream trajectory of software development, from open and ambiguous applications to closed and single-purpose apps, I see that day coming. In order to resist or at least postpone this future, I intentionally create animated GIFs that not only rely on a browser running in the background, but require one to be visible.

For example, the animation in Summer2929 Olia Lialina, Summer, 2013, http://b-o.fr/summer requires the location bar to be visible, Hosted3030 Olia Lialina, Hosted, 2020, http://b-o.fr/hosted depends upon a user being able to open other tabs, Self-Portrait3131 Olia Lialina, Self-Portrait, 2018, http://olia.lialina.work/ will not work if you do not have three different browsers installed on your computer, Best Effort Network3232 Olia Lialina, Best Effort Network, 2015/2020, https://best.effort.network/ will only make sense if you have more than one browser window open on your computer. In addition, the deliberate use of scrollbars can be a way to shift attention to the browser. I was happy that, last semester in my Get Out of the Loop seminar, students included scrolling in the scripts for their animations.3333 See: Marla Schneider, Broadway Scroll, 2020, http://b-o.fr/schneider

Also Cora Lenz and Amelie Vogelmann, How Far Can You Go, 2020, http://b-o.fr/lenz-vogelmann You may also want to visit Dragan Espenschied’s Gravity the piece that augments legendary vernacular graphics with the movement of the scrollbar, thus paying tribute to both. The third tactic to emphasize the browser can be borrowed from artists and coders who use the Resize Window feature to animate the object on the screen, from the viral Garmoshka3434 Art Polikarpov, Garmoshka, 2012, http://b-o.fr/garmoshka by Artem Polikarpov, to the Ragepage3535 Fabien Mousse, Ragepage, 2011, http://b-o.fr/ragepage miniature by Fabien Mousse. In Black Room,

Cassie McQuater’s browser-based game that is a paean to the Web, the players have to drag along the bottom right corner of the browser, as it is the only way to uncover the objects in the rooms.

Perhaps we are not too late! Maybe there is a chance to prolong the lives of webpages and Web browsers. This is what I also thought in 2005 when I literally offered myself up in the form of “perfect” GIFs for webpages and added danceol.gif  , accordiol.gif

, accordiol.gif  , and hulaol.gif

, and hulaol.gif  to all the free GIF collections I could reach.3636 Olia Lialina, Animated GIF Model, 2005, http://b-o.fr/agm By “perfect” I meant perfectly looped movement and clear cutout. My plan was to have them be used on personal home pages, but people were not making those anymore, so I ended up on forums, Tumblr, Livejournal and small business websites whose authors had ignored the advice of usability experts and web design evangelists to avoid animated GIFs by all means.3737 In 2012, after Google introduced the Search by Image function, I could find the forums, posts and webpages which used my work. My findings are captured in Memoirs, available as a playlist at http://b-o.fr/memoirs1

to all the free GIF collections I could reach.3636 Olia Lialina, Animated GIF Model, 2005, http://b-o.fr/agm By “perfect” I meant perfectly looped movement and clear cutout. My plan was to have them be used on personal home pages, but people were not making those anymore, so I ended up on forums, Tumblr, Livejournal and small business websites whose authors had ignored the advice of usability experts and web design evangelists to avoid animated GIFs by all means.3737 In 2012, after Google introduced the Search by Image function, I could find the forums, posts and webpages which used my work. My findings are captured in Memoirs, available as a playlist at http://b-o.fr/memoirs1

GIF Animation Studio book is an exception. Negative and arrogant judgments, on the order of “the more animated GIFs on a page, the suckier the page,”3838 Vincent Flanders and Michael Willis, Web Pages That Suck, (Haboken: Sybex Inc., 1998), 87. or “animation for its own sake is charmless, abrasive, and amateurish,”3939 Jeffrey Zeldman, Taking Your Talent to the Web, (Indianapolis: New Riders Publishing, 2001), 238. are to be found in every web design manual we have in the GeoCities Research Institute Library.4040 More examples in Olia Lialina, GIFs, Animated GIFs and GIFs formerly known as Animated, 2014, http://b-o.fr/lialina4 GIFs were seen as an inappropriate format for the clean, professional Internet already surfacing in the mid-1990s. By the end of the 1990s they had been swept off the Web. They made a comeback by the end of the 2000s, partly as a response to the growing attention to digital folklore and Web vernacular, mostly as a form of “ubiquitous mini cinema,” which, as it happens, was only the beginning of the overall cinemafication of online design4141 Tom Moody, IMG MGMT: Psychotronic GIFs, 2008, http://b-o.fr/moody: looped excerpts from films, TV shows, animated photographs and paintings brought to life, glittering cards, all posted, embedded, or attached. Since then GIFs can be found everywhere and there is no message that cannot be turned into one or communicated by one. They are unavoidable and indestructible. The animated GIF […] has proven its resilience as a zombie file format; no matter how many times this file format dies, it continues to be reborn, renewed, and intensified.4242 Katrina Sluis, “As We May <Blink>,” in Olia Lialina: Net Artist, (Dijon: Les Presses du Réel, 2020), 172.

In 2014, in an attempt to address and preserve their complex history, I began to assemble a timeline of animated GIFs that immediately forked into two categories, official and alternative. The timelines are subjective and formalistic; they are a work in progress that requires comments. I will conclude this article with links to them—to loop the text, send the reader back to the title and explain what I mean with my exhortation to see the difference between GIFs, and, what I suggest, not without irony, are animated JPEGs.

An animated JPEG is a posted looped moving image that is sometimes saved as a GIF file.  Two viral animations, Le-Mepris.gif* and Mad-Men.gif*, were catalysts for me as a researcher, the point when I realized that, as of the beginning of the 2010s, the technique and, above all, the role of GIFs have changed. Animation has become more important than transparency, content and structure have become narrative and cinematic. The Mad Men GIF even has an end, although the loop is infinite. They are clear references to film. There were clearly no references to any other objects next to them on the pages where I found them. These GIFs were not made as building blocks for a webpage and the Internet—they were standalone. Animated JPEGs had emancipated themselves from the subjective logic of amateur collections. They were produced, collected, and enriched with metadata to be optimized for keyword search and the tracking of user behavior, which turned them into valuable actors of platform capitalism. This is why Google bought Tenor4343 Kathleen Chaykowski, “Google to Acquire Startup Tenor as Mobile GIF-Sharing Explodes,” http://b-o.fr/chaykowski in 2018 and Facebook acquired Giphy for no less than 400 million USD in 2020.4444 As Mark Sullivan writes in “The Real Reason Facebook Bought Giphy for $400 Million,” 2020, http://b-o.fr/sullivan “One of the biggest values in the deal for Facebook might be data. Already, 50% of Giphy’s traffic comes from Facebook apps. But now Facebook will know what Giphy GIFs people are sharing in all the other apps that use Giphy’s database, including Apple’s iMessage, Snapchat, Telegram, and TikTok.”

Two viral animations, Le-Mepris.gif* and Mad-Men.gif*, were catalysts for me as a researcher, the point when I realized that, as of the beginning of the 2010s, the technique and, above all, the role of GIFs have changed. Animation has become more important than transparency, content and structure have become narrative and cinematic. The Mad Men GIF even has an end, although the loop is infinite. They are clear references to film. There were clearly no references to any other objects next to them on the pages where I found them. These GIFs were not made as building blocks for a webpage and the Internet—they were standalone. Animated JPEGs had emancipated themselves from the subjective logic of amateur collections. They were produced, collected, and enriched with metadata to be optimized for keyword search and the tracking of user behavior, which turned them into valuable actors of platform capitalism. This is why Google bought Tenor4343 Kathleen Chaykowski, “Google to Acquire Startup Tenor as Mobile GIF-Sharing Explodes,” http://b-o.fr/chaykowski in 2018 and Facebook acquired Giphy for no less than 400 million USD in 2020.4444 As Mark Sullivan writes in “The Real Reason Facebook Bought Giphy for $400 Million,” 2020, http://b-o.fr/sullivan “One of the biggest values in the deal for Facebook might be data. Already, 50% of Giphy’s traffic comes from Facebook apps. But now Facebook will know what Giphy GIFs people are sharing in all the other apps that use Giphy’s database, including Apple’s iMessage, Snapchat, Telegram, and TikTok.”

Animated JPEGs of Mad Men and Le Mépris could be saved and reproduced and played outside of a browser. Technically they would not even have to be GIFs. As of 2020, they are no longer. What we now call GIFs are files initially saved in .mp4 or .webM formats. Imgur has been “automagically” converting GIF uploads into videos since 2014. Instagram, Twitter and some content management systems do the same with the GIFs we post. This conversion is not only changing their file size, it also slaps interface elements over them, allowing and inviting users to “play” and “pause” the animations. Also, since the h264 video codec used in MP4 files does not support transparency, transparent pixels are replaced with a solid color, so transparency is now history.

Giphy’s meta name refers to the site as “your top source for the best and newest GIFs and animated stickers online,” and is correctly defined by Wikipedia as a platform for “short looping videos with no sound that resemble animated GIF files.”4545 http://b-o.fr/giphy While the lack of sound still applies to Giphy, in fact GIFs with sound have arrived. They appeared in 2013 on Vine.com, a service that introduced a six-second video loop format. It was discontinued in 2017, but since 2016 we have TikTok, a more complex social media product with a loop that can be as long as fifteen seconds. Still, in spirit, these remain the same old “GIFs with sound.” Who would think that this unintentional aphorism, that in 2011 unleashed a storm of jokes (see footnote 5), would become a comprehensible term and legit search request as of November 2020.4646 “Modern GIFs have the ability to carry audio and are preferred. The technology is absolutely new, and now you can even add music to GIF files,” http://b-o.fr/filmora Not to mention that “GIFs with Sound” is the top trending category on Gfycat.

Gfycat, the youngest of GIF-sharing platforms (2015) says its mission is to “improve the GIF viewing experience” and “upgrade the GIF viewing experience for the 21st century” which means video, sound, and interaction, among other things. None of which were qualities possessed by original GIF files. As they wisely mention on the same About page: “Even if delivered by video, the GIF is always there.” A very true observation, though I would contradict it and say that it is not the GIF but rather the loop that is present, and looping is not true to the original nature of the GIF.

In summary, this is why I use and advocate for the paradoxical if not absurd term “Animated JPEG.” I hope to redirect our attention from the objects that move, blink, glitter and lip sync before our bemused eyes to the process that lies behind them, namely the alienation of Internet users from their medium. I continue to hope that not only GIFs, but the idea that you can use them to build your own individual corner of cyberspace, will return.

* These GIFs could not be reproduced in this issue.