Was there design before DTP? How did one work without computers? In order to gainsome insights, we met with Etienne Robial, a graphic designer and artistic director who has been doing his thing since 1970.

Back Office Your career has enabled you to pass through several technical periods. Could you tell us how you worked before the advent of desktop publishing (DTP)?

Etienne Robial To start with, there’s always pencil and paper. Today, in 2016, one still has to design with these tools, quite simply because the rules of layout and visual perceptions are strictly the same. I’ve always found it more rewarding to work by hand, because this enables you to play directly with grids, moiré effects, contrasts, the brightness of inks, etc. You can give yourself a new look with your screen.

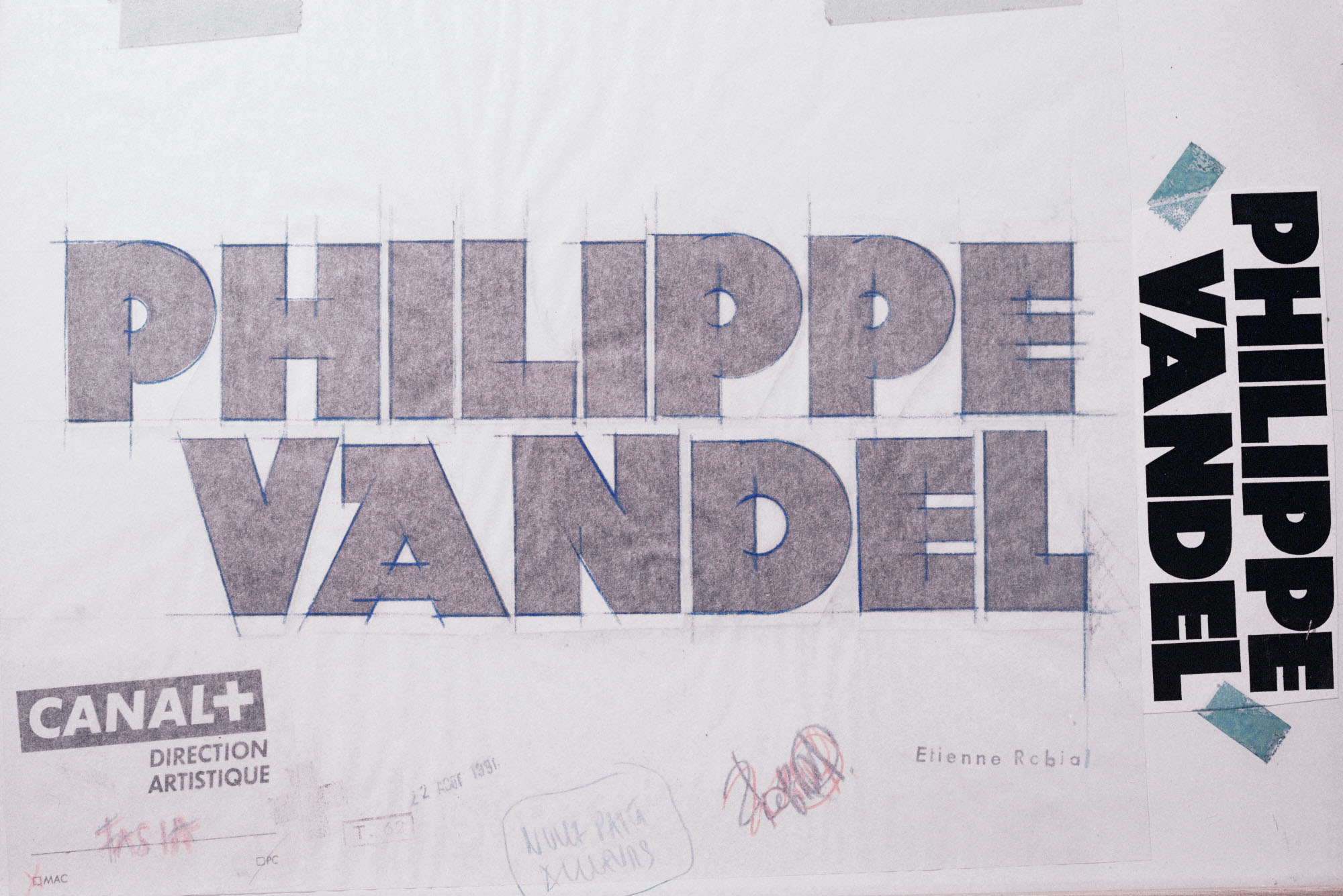

Before DTP, the first stage was working in blue pencil. Everything we could use for sketches, dimensions and layout references was drawn in blue pencil, sometimes on graph paper, which was also blue. Why? Because films are sensitive to red and blue doesn’t appear when you shoot, so you can scribble away with your pencil as much as you want. When I’m happy with my work in blue, I move on to black. For example, you can also draw with India ink using a brush, pen or ruling pen. A ruling pen, as the name suggests, makes it possible to draw rules. You adjust the thickness of the line with a scroll wheel and, depending on the type, you fill them with gouache or ink. I particularly like the Pelikan Graphos models, which are more refined than ordinary ruling pens and make rules of 0.10 mm perfectly. That was before the Rotring! To draw broad lines, the best thing is to use a charrue (a large ruling pen) or simply go along them with a liner brush, which is a brush made with the long hairs from a calf’s ear. Even if your hand shakes, your rule remains flawless. This kind of tool brings the lines to life and it’s definitely different from Mac layouts, which are all cut and dried and a bit too straightforward.

These are the tools of my trade, so I’m attached to them. Today I still work with them: my blue pencil is always on my desk. When I’m working, I work on paper, not on Mac: drawing, pencil, eraser… the eraser is a sign of humility! I always take a toolbox with me on holiday with the basic essentials.  My emergency kit contains a Criterium, a blue pencil, a pencil sharpener, and lots of other things. Ah! There’s also some Lexomil®, because you need that if you don’t want to end up throwing the client out the window.

My emergency kit contains a Criterium, a blue pencil, a pencil sharpener, and lots of other things. Ah! There’s also some Lexomil®, because you need that if you don’t want to end up throwing the client out the window.

B O You collect all sorts of tools… 22 See the lecture “Faire Collection!” given by Etienne Robial on October 1, 2015 at the Pompidou Center as part of the *Parole au Graphisme* series. Voir/See: http://b-o.fr/collection How do they influence the way you work?

E R These tools are very important to me. For example, I’ve got lots of boxes of colored pencils, all in different shades, which I use as personal color charts; I fill up notebooks with them, and they help me in my work. For example, some color ranges for TV credits I’ve made come almost entirely from Pearl colored pencils. I find corresponding equivalents in Pantone, CMYK and RGB.

B O Do you use the same colored pencils and drawing pens when working the letters?

E R In fact it’s quite easy to wipe letters clean by hand. In this particular case one uses a brush. When I was in Switzerland, notebooks were filled with Helvetica. Later on I also used Letraset and cutout alphabets that came from my collections of letter design catalogues used by sign painters. There’s a bit of everything, modern letters, artistic letters, I’ve got thousands of them! Over time, I’ve made myself a palette of tools made of bromides 33 Photographic print in black or white, with no shades of grey. from thirty-odd alphabets which I use as bases for my books and credits. Bromides are like originals that you’re not entitled to touch or tinker with. You duplicate them on film or paper, you cut them out and you stick them on your layouts. For example, for the credits for the CANAL+ program Nulle Part Ailleurs in the mid-1980s, I made 99%, 100% and 101% photocopies and I set the letters by eye and by hand 44 Regarding Robial’s work for CANAL+, see:Etienne Robial, CANAL+. Image graphique et identité visuelle (Paris: Albin Michel, 2001).. The visual intention must be conveyed by the hand, when it’s the eye that draws and not the tool.

Bromides are like originals that you’re not entitled to touch or tinker with. You duplicate them on film or paper, you cut them out and you stick them on your layouts. For example, for the credits for the CANAL+ program Nulle Part Ailleurs in the mid-1980s, I made 99%, 100% and 101% photocopies and I set the letters by eye and by hand 44 Regarding Robial’s work for CANAL+, see:Etienne Robial, CANAL+. Image graphique et identité visuelle (Paris: Albin Michel, 2001).. The visual intention must be conveyed by the hand, when it’s the eye that draws and not the tool.  So Nulle Part Ailleurs is never written the same way, the letters dance, and there’s life there.

So Nulle Part Ailleurs is never written the same way, the letters dance, and there’s life there.

B O A propos, for television, how were these physical montages transposed to the screen?

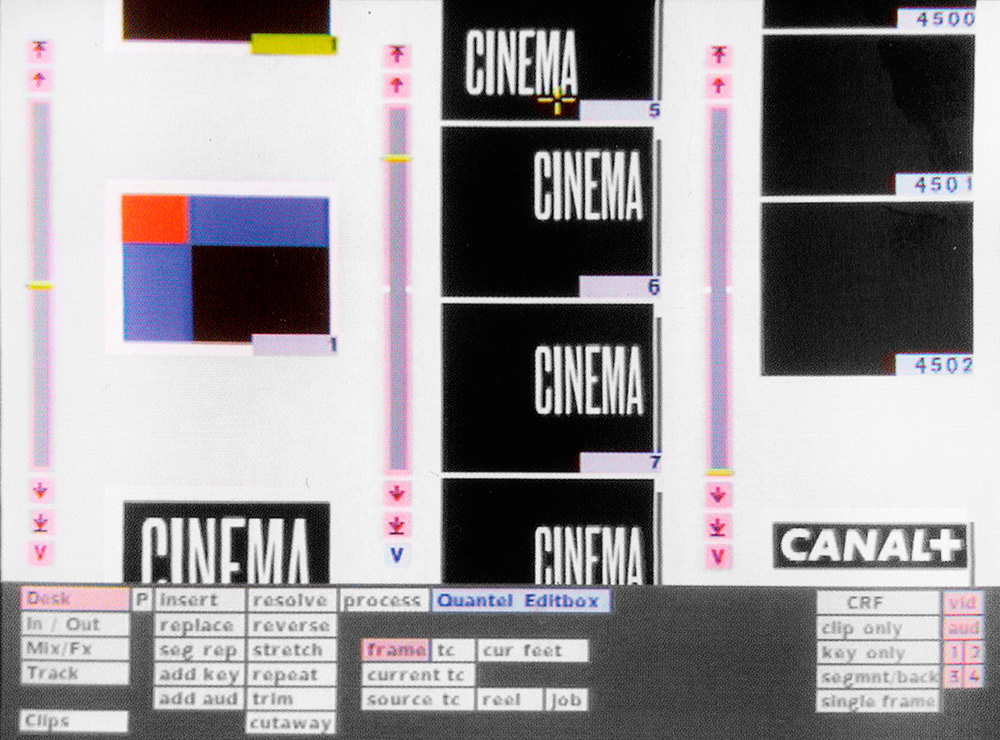

E R In the 1980s, to do animation, you would photograph the layouts on a vertical camera connected to a Paintbox. 55 A computer workstation specializing in video composition and special effects for television including, in particular, a graphic palette. This term, which has become widespread, originated with the first machine of this type: the Quantel Paint Box, which appeared in 1981. It was a large machine with a stylus: like a graphics tablet, but for TV… At CANAL+, I worked with Fasia Lamari, my paint box operator, who used an Editbox from Quantel; not the sort of gear used by the man in the street, as it’s outrageously expensive and very complicated to use. You have to realize that these machines were earmarked for broadcast use, meaning they were designed for productions that could be broadcast all over the world. Every TV station had them… We used them to handle what had been photographed, put in colors, retouch, create animation, and so on. Once the credits were in place, they were recorded on the Paintbox and, normally, there was no longer any way of keeping any record of them, other than videotaping them. In order to remember things, I took photos with a Polaroid, several hundred a day, of each picture of each animation.

At CANAL+, I worked with Fasia Lamari, my paint box operator, who used an Editbox from Quantel; not the sort of gear used by the man in the street, as it’s outrageously expensive and very complicated to use. You have to realize that these machines were earmarked for broadcast use, meaning they were designed for productions that could be broadcast all over the world. Every TV station had them… We used them to handle what had been photographed, put in colors, retouch, create animation, and so on. Once the credits were in place, they were recorded on the Paintbox and, normally, there was no longer any way of keeping any record of them, other than videotaping them. In order to remember things, I took photos with a Polaroid, several hundred a day, of each picture of each animation.

In 1986, when my wife, Florence Cestac, had Jules, I discovered Sony Prints. We had gone to have an ultrasound, the guy put his probe on her belly and hey, there was a boy! Then, right there in his office, he gave me some small photos to take home. I asked him: “How did you do that?” I set out to find the same machine, and I got CANAL+ to buy it, and called the technician who adapted the signals of my control screens for the Sony Print, which was designed for receiving the signals of an ultrasound probe… It’s important to bear in mind that graphic palettes were not personal computers, you couldn’t print them, it was all part of the broadcast. The Sony Print enabled me to keep a printed record of what was produced on a palette in a relatively faithful way. The CNAP (Centre National des Arts Plastiques) has notebooks full of these images. I shot almost every image of each set of credits—when we made credits with the names of the 200 people involved, that made for a whole lot of images! Sometimes I also reused those printed records to make paper documents like press packets and invitations. We did things the wrong way round!

B O Was it the same for all the texts?

E R No, composition by hand was mainly used for the credits, and the titling. At CANAL+, the bulk of the texts were composed onsite on special writing synthesizers which were only used for that, and just had the Futura Canal+ font. I had designed templates that defined the placement of the inlays, and the texts were entered directly onsite.  If you take a look at that, you can see all the typesetting, the grey charts, the safety zones, etc. The charts helped to test the rendering of the greys, the black of CANAL+, etc. CANAL+ black is special, it’s not pure. My dear students make me beautiful pure black flat tints on their Macs. If you do that on TV, automatic systems launch a scrolling banner that reads: “Please excuse us, we are having technical difficulties,” because the beautiful black flat tint is interpreted as an absence of signal. A Mac is not made for broadcast, it’s there for making layouts, but what you produce with it can’t be broadcast, which is a pity!

If you take a look at that, you can see all the typesetting, the grey charts, the safety zones, etc. The charts helped to test the rendering of the greys, the black of CANAL+, etc. CANAL+ black is special, it’s not pure. My dear students make me beautiful pure black flat tints on their Macs. If you do that on TV, automatic systems launch a scrolling banner that reads: “Please excuse us, we are having technical difficulties,” because the beautiful black flat tint is interpreted as an absence of signal. A Mac is not made for broadcast, it’s there for making layouts, but what you produce with it can’t be broadcast, which is a pity!

B O You’ve also done a lot of work designing books, in particular with Futuropolis. What differences are there compared to technical TV procedures?

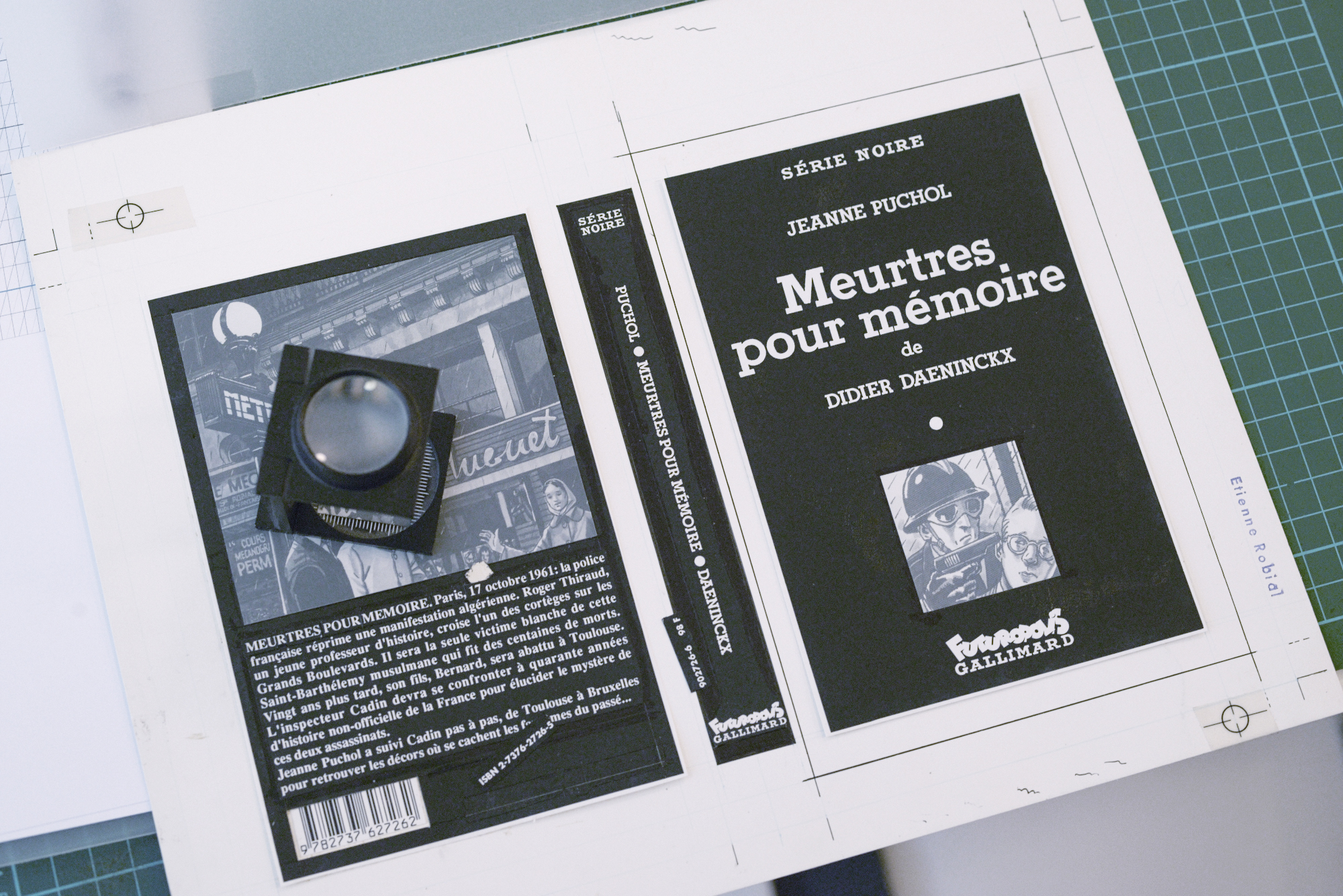

E R In phototypesetting, for books, the starting point is the same as for TV: you have your dimensions, your template, in which the placement of a block of text is defined. To choose an alphabet, you look through a typesetter’s catalogue and, depending on the width of the block and the type size, you work out the number of lines that you can fit in the height of the block with a line gauge. This is a kind of graded ruler which gives you the equivalences between a measurement and a number of lines in a given type size. Then you send your typewritten text to the typesetter with all the instructions (font, size, drop cap, column width, etc.) and a small explanatory sketch. In return, the composer gives you back a straight keyed text, on a long strip of paper, which you cut into blocks and glue with rubber cement where required. On your Mac, you can vary the scale of the characters: the same letter design is then used just as well in 6-point as in 72-point type, and you can play around with your line spacing any way you want. Thanks for nothing, Adobe!

For the Futuropolice Nouvelle collection in the early 1980s, the rule was that all the books had to have the same format of forty-eight pages to reduce the cost of production. Based on the length of the text, I therefore had to vary the character and the type size used so that the text fitted perfectly into the layout. To do this, everything had to be precisely calculated, and that required a line gauge. Over and above the new text composition, this cheap and technical design formula, thrashed out with the manufacturer, was helpful when it came to balancing the publishing house’s budget.

B O Futuropolis is well known to comic strip enthusiasts. How did you go about creating those publications?

E R It’s important to bear in mind that photographic and photomechanical procedures were everywhere, in every agency and publishing house. Most of them had a Repromaster a reproduction camera from Agfa making it possible to enlarge, reduce and screen a document. It’s a sort of vertical large format camera with the original at the bottom, in the middle a large lens, and at the top a piece of glass housing a photosensitive surface, film or paper (bromide). In the dark, all you have to do is to adjust the reproduction size, focus with a linen tester on the upper glass and shoot. With this machine, it was practical to use a Proportion Scale, a kind of disk, pivoting in the middle, which gives you the scale ratio between two documents. People used the Repromaster all the time.

For the comic strip albums published by Futuropolis, there’s basically a black-and-white drawing to scale which is exposed on film with a Repromaster. Then you make a film for each color (marked with black) on which you stick inactinic film that creates solid tints or Benday halftone screens that will give you levels of grey. 1212 Which does not produce photochemical reactions. These fixed screens have a special pattern and are listed in an associated catalogue giving the equivalences of each density in percentages of colors. It’s very limited: you can only work with spot colors, but it’s possible to overprint the screens to make mixtures of them. On the other hand, you yourself manage the orientations and thus the moiré and rosette effects. 1313 The motif resulting from the superposition of several halftone screens (four in CMYK) whose orientations differ (rosette). There are also graded screens from white to black in Letraset transfers. They cost about two or three euros a sheet and you waste a whole lot of them. With things like that, you expose them on the repro camera so as to make cheap ones. Sometimes I’ve also designed my own screens, where anything and everything can be used: fabrics, motifs, materials, etc. With Joost Swarte, the comic strip author, we also experimented with what postwar photo-engravers used to make random halftone screens—laying varying amounts of gum arabic on a zinc sheet plunged in acid. The more gum you used, the more the crystallization is blocked, and the lighter the grid.

Reproducing a photo was a bit different: you had to insert a magenta screen 1515 A halftone screen on film where each dot is a radial magenta gradient. Used with ortho-litho film (without shades of grey), a magenta screen made it possible to obtain a screened image from a document in continuous tones. with the lineature 1616 Scale of a printing screen, defined by number of lines per inch. that you wanted against the sensitive surface placed on the glass. That gave you the halftone screened photo on the right scale to be glued to your layout.  One must not forget that, prior to DTP, all layouts were documents made from cutouts that were stuck on and reproduced, and that the work was manual. It’s not for nothing that photomontage was very present in the images of the time. All those layouts were exposed on film to the right scale, then imposed.

One must not forget that, prior to DTP, all layouts were documents made from cutouts that were stuck on and reproduced, and that the work was manual. It’s not for nothing that photomontage was very present in the images of the time. All those layouts were exposed on film to the right scale, then imposed.

B O So were you working on the actual films themselves?

E R Yes, we did that on enormous 70 × 100 cm light tables so as to work directly at the size of the offset plate and expose to scale. You retouch by scratching the black with a vaccine point (vaccino-stylus), the way you used to do with scratch cards in another era, or you block areas with gouache or inactinic film. 1717 Black backed surface showing white areas where it is scratched. Then pens using inactinic ink were invented, like small felt tips, and that was a revolution!

Once the films are ready, the problem is that you only see the result of the overlaid colors at the bottom of the machine. If I’d had some money, I could have afforded Chromalins, transparent prints, color by color, which give you back the final rendering prior to printing. This enables you to check to make sure you haven’t made any mistakes, that you haven’t put the title La Guerre des Boutons in blue rather than red. In this type of work, there are four films because it’s four-color: cyan, magenta, yellow and black. This color by color work permitted complete management of each printing plate. The year 1987 saw the arrival of the first scanners for full-color photoengraving, which gave you a separation based on a color photo… Look at that piece of shit! When you compare this thing with a manually managed separation, it’s not a pretty sight! My trade is working with color. All Futuropolis publications are printed in black and white, but each black is different, blended for each comic-strip author: Tardi, much thicker and more coal-black, needs something hot. On the other hand, when Joost Swarte makes me a very “clear line” thingy, I’ll add some blue. I note how much blue I put, and that color is henceforth called Swarte black. You can get up early to appreciate these subtleties on the screen. Today I’m still experimenting with my Riso duplicopier, a machine initially meant for printers and reprographers, with which I have fun, creating new textures and a whole system of random screens that is not far removed from what I was playing around with in Swarte’s work.

B O Don’t you think the computer can create other ways of doing things?

E R In 1984, I had the first Macintosh, but it was for tinkering, seeing what you could do with it. What interested me was to be able to take advantage of that machine—let’s call them machines rather than tools—the way you do with a pencil and paper, when you want to draw something. Nowadays, the Mac and the most widely used software packages have been designed to produce imitations, except that the whole tactile relationship with work on paper that you can have disappears. At the end of the day, what are computers for, per se? The computer is a practical tool which everyone has. One has merely to pirate a copy of Illustrator or Photoshop, and, with a bit of curiosity, anyone can be a graphic designer!

Interview conducted by Kévin Donnot and Élise Gay in Paris, on May 4th 2016.